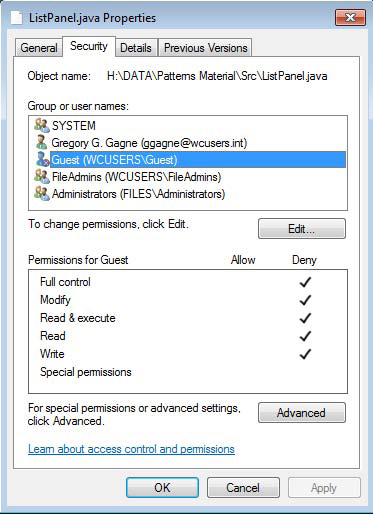

11.2.1 Sequential Access

- A sequential access file emulates magnetic tape operation, and generally supports a few operations:

- read next - read a record and advance the tape to the next position.

- write next - write a record and advance the tape to the next position.

- rewind

- skip n records - May or may not be supported. N may be limited to positive numbers, or may be limited to +/- 1.

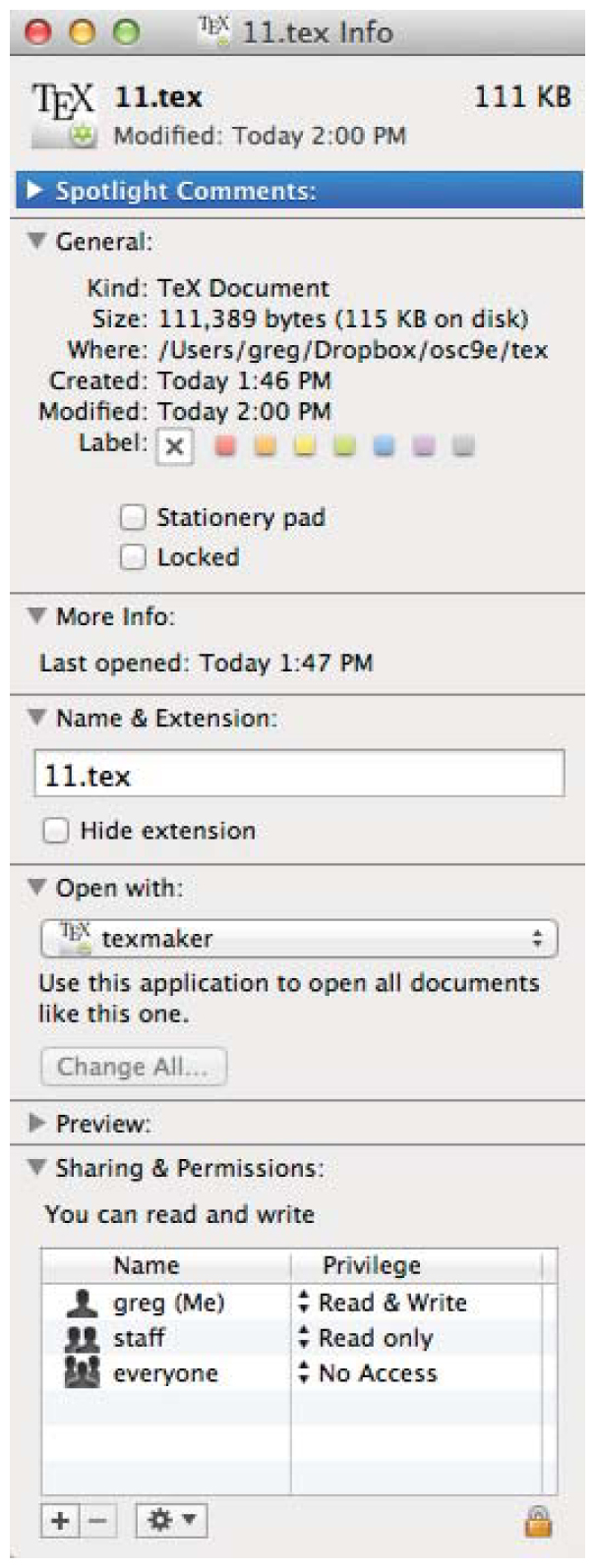

Figure 11.4 - Sequential-access file.

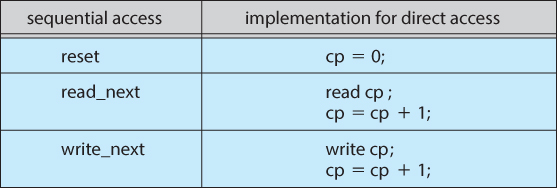

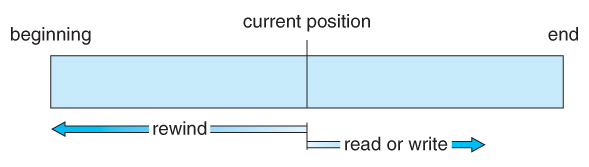

11.2.2 Direct Access

- Jump to any record and read that record. Operations supported include:

- read n - read record number n. ( Note an argument is now required. )

- write n - write record number n. ( Note an argument is now required. )

- jump to record n - could be 0 or the end of file.

- Query current record - used to return back to this record later.

- Sequential access can be easily emulated using direct access. The inverse is complicated and inefficient.

Figure 11.5 - Simulation of sequential access on a direct-access file.

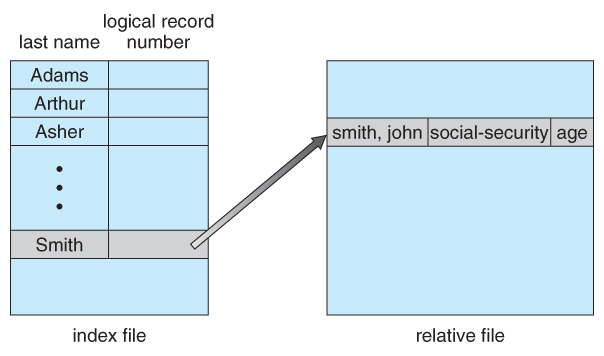

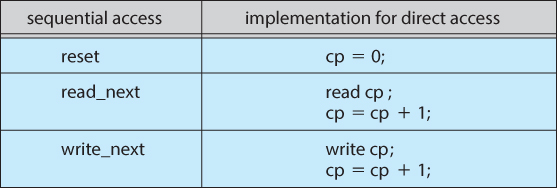

11.2.3 Other Access Methods

- An indexed access scheme can be easily built on top of a direct access system. Very large files may require a multi-tiered indexing scheme, i.e. indexes of indexes.

Figure 11.6 - Example of index and relative files.

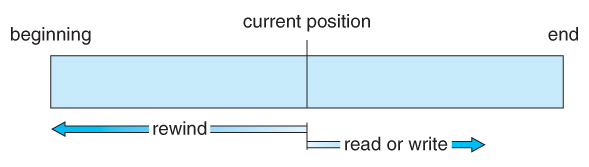

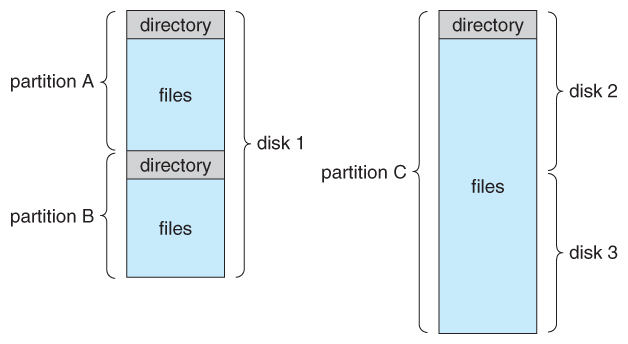

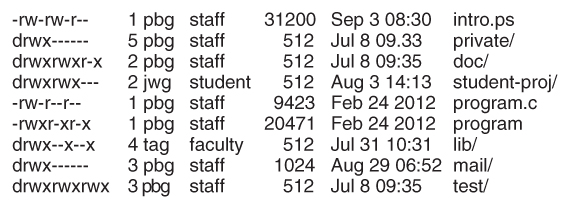

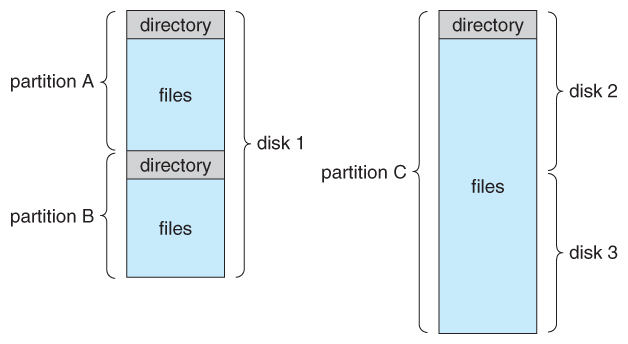

11.3.1 Storage Structure

- A disk can be used in its entirety for a file system.

- Alternatively a physical disk can be broken up into multiple partitions, slices, or mini-disks, each of which becomes a virtual disk and can have its own filesystem. ( or be used for raw storage, swap space, etc. )

- Or, multiple physical disks can be combined into one volume, i.e. a larger virtual disk, with its own filesystem spanning the physical disks.

Figure 11.7 - A typical file-system organization.

11.3.2 Directory Overview

- Directory operations to be supported include:

- Search for a file

- Create a file - add to the directory

- Delete a file - erase from the directory

- List a directory - possibly ordered in different ways.

- Rename a file - may change sorting order

- Traverse the file system.

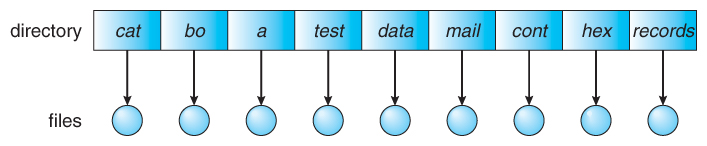

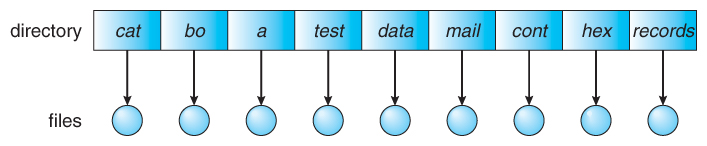

11.3.3. Single-Level Directory

- Simple to implement, but each file must have a unique name.

Figure 11.9 - Single-level directory.

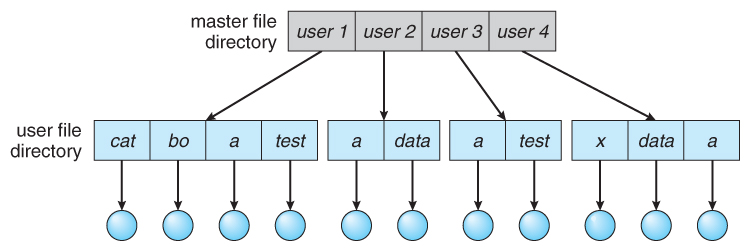

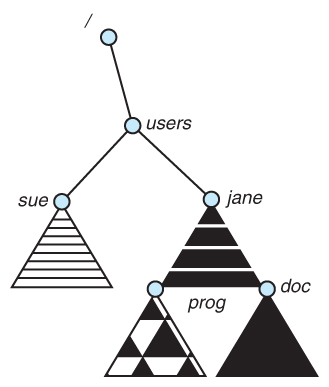

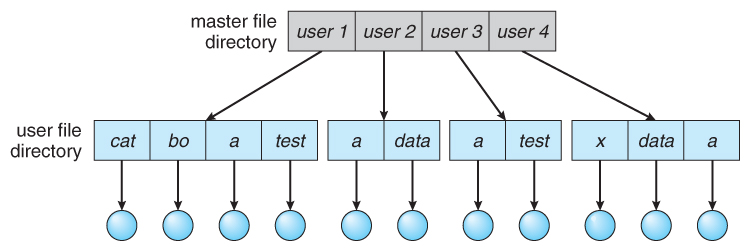

11.3.4 Two-Level Directory

- Each user gets their own directory space.

- File names only need to be unique within a given user's directory.

- A master file directory is used to keep track of each users directory, and must be maintained when users are added to or removed from the system.

- A separate directory is generally needed for system ( executable ) files.

- Systems may or may not allow users to access other directories besides their own

- If access to other directories is allowed, then provision must be made to specify the directory being accessed.

- If access is denied, then special consideration must be made for users to run programs located in system directories. A search path is the list of directories in which to search for executable programs, and can be set uniquely for each user.

Figure 11.10 - Two-level directory structure.

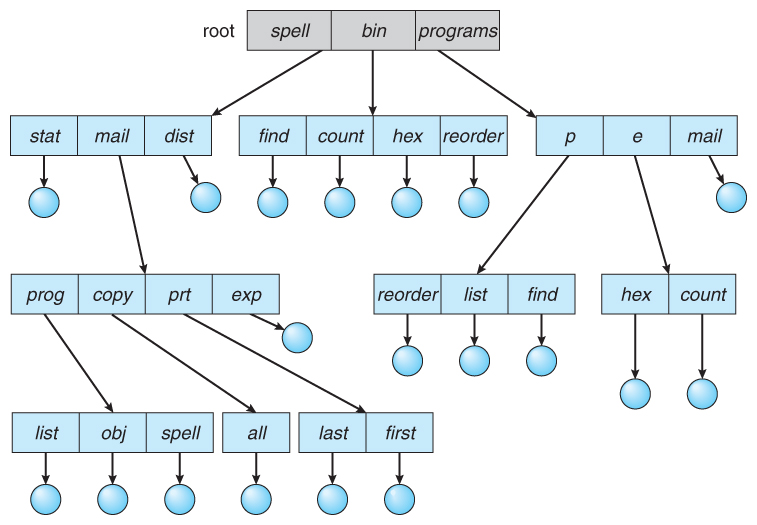

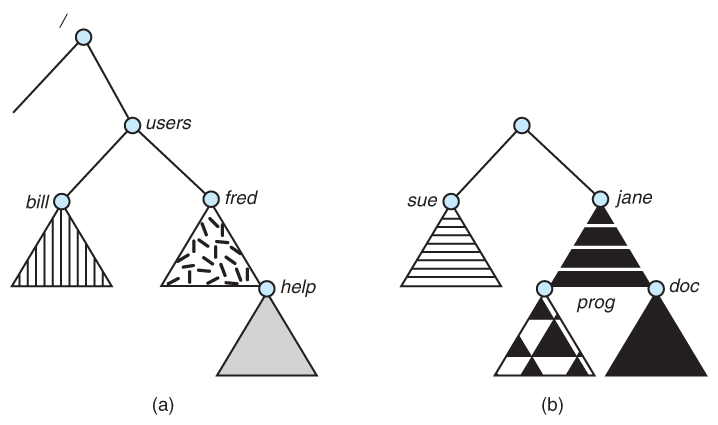

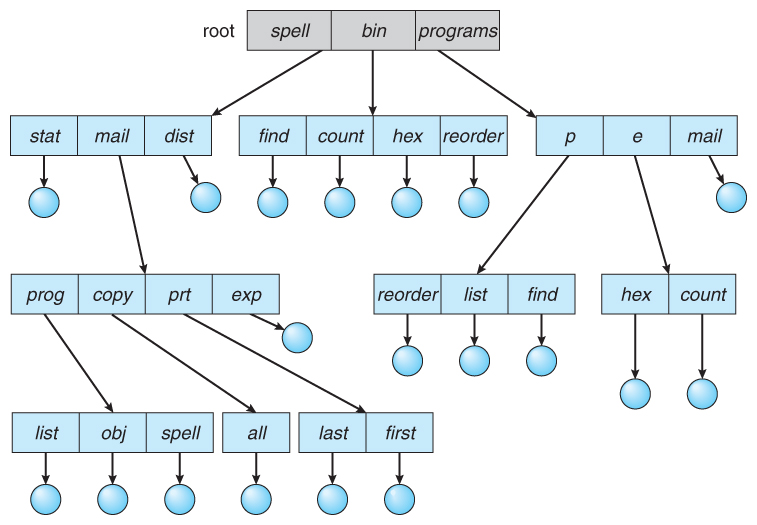

11.3.5 Tree-Structured Directories

- An obvious extension to the two-tiered directory structure, and the one with which we are all most familiar.

- Each user / process has the concept of a current directory from which all ( relative ) searches take place.

- Files may be accessed using either absolute pathnames ( relative to the root of the tree ) or relative pathnames ( relative to the current directory. )

- Directories are stored the same as any other file in the system, except there is a bit that identifies them as directories, and they have some special structure that the OS understands.

- One question for consideration is whether or not to allow the removal of directories that are not empty - Windows requires that directories be emptied first, and UNIX provides an option for deleting entire sub-trees.

Figure 11.11 - Tree-structured directory structure.

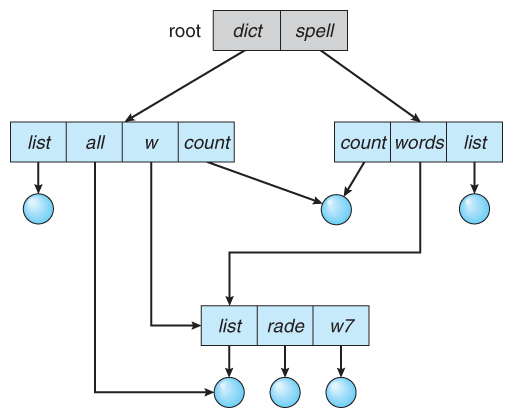

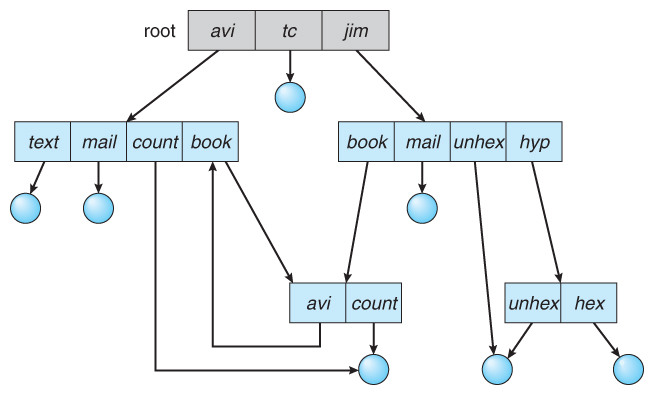

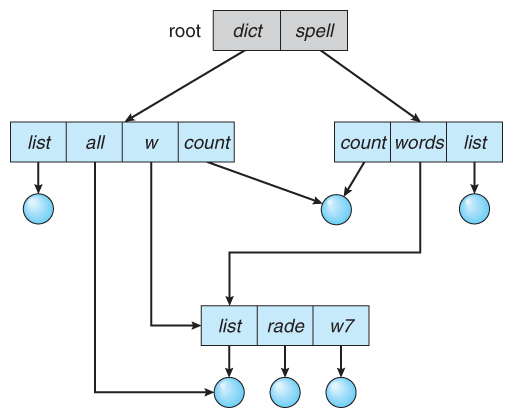

11.3.6 Acyclic-Graph Directories

- When the same files need to be accessed in more than one place in the directory structure ( e.g. because they are being shared by more than one user / process ), it can be useful to provide an acyclic-graph structure. ( Note the directed arcs from parent to child. )

- UNIX provides two types of links for implementing the acyclic-graph structure. ( See "man ln" for more details. )

- A hard link ( usually just called a link ) involves multiple directory entries that both refer to the same file. Hard links are only valid for ordinary files in the same filesystem.

- A symbolic link, that involves a special file, containing information about where to find the linked file. Symbolic links may be used to link directories and/or files in other filesystems, as well as ordinary files in the current filesystem.

- Windows only supports symbolic links, termed shortcuts.

- Hard links require a reference count, or link count for each file, keeping track of how many directory entries are currently referring to this file. Whenever one of the references is removed the link count is reduced, and when it reaches zero, the disk space can be reclaimed.

- For symbolic links there is some question as to what to do with the symbolic links when the original file is moved or deleted:

- One option is to find all the symbolic links and adjust them also.

- Another is to leave the symbolic links dangling, and discover that they are no longer valid the next time they are used.

- What if the original file is removed, and replaced with another file having the same name before the symbolic link is next used?

Figure 11.12 - Acyclic-graph directory structure.

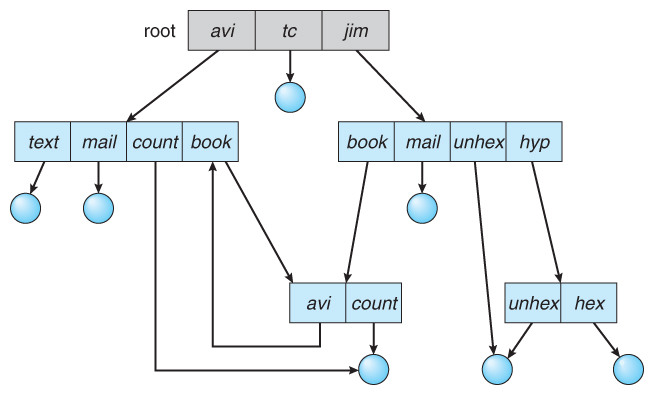

11.3.7 General Graph Directory

- If cycles are allowed in the graphs, then several problems can arise:

- Search algorithms can go into infinite loops. One solution is to not follow links in search algorithms. ( Or not to follow symbolic links, and to only allow symbolic links to refer to directories. )

- Sub-trees can become disconnected from the rest of the tree and still not have their reference counts reduced to zero. Periodic garbage collection is required to detect and resolve this problem. ( chkdsk in DOS and fsck in UNIX search for these problems, among others, even though cycles are not supposed to be allowed in either system. Disconnected disk blocks that are not marked as free are added back to the file systems with made-up file names, and can usually be safely deleted. )

Figure 11.13 - General graph directory.